Today, the battle for market shares is being fought at the expense of the weakest links in the food production chain

The Agrifood Atlas warns that the monopolising of the food chain by “ever-fewer-ever-larger” corporations has far reaching consequences for our food system. The Agrifood Atlas compiled by the Heinrich Böll Foundation [https://www.boell.de/en], the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation [https://www.rosalux.de/en/] and Friends of the Earth Europe [http://www.foeeurope.org/] stresses the fact that agrifood corporations foster industrialisation along the entire global value chain, i.e. along the farm-to-plate chain. Moreover, corporate purchasing and sales policies advocate a form of agriculture that predominantly centres around productivity.

Concentration and monopolisation also promote the unstoppable onward march of industrial agriculture and inevitably therefore its associated effects on the environment and climate. The loss of soil fertility and biodiversity, the uncontrolled pollution of marine and estuarine ecosystems and above all the worrying greenhouse gas emissions [Pussemier & Goeyens 2017] are most noticeable negative repercussions of the spread of industrial farming. But despite these concerns the rate of consolidation in the agrifood sector continues to accelerate. Unfortunately, there is hardly any reorientation in sight. On the contrary, attempts to produce binding rules concerning human rights, working conditions and environmental quality are often undermined.

Neither protectionism nor deregulation has ever permanently slowed down the growth rate of the agrifood industry. Mergers make firms bigger. The first large agricultural corporations with global reach emerged at the end of the 19th century in Britain, which was then the world’s dominant commercial power. Farm labour was to a large extent mechanised. Agrochemicals were invented and marketed. Trains, ships, and planes revolutionised freight transport. And new technologies improved both the preservation and storage of food products. Free trade removed tariff barriers and capital shortages were overcome by selling crops even before the seeds had been put in arable soil.

Scientific investigation of fertilisation was launched around 1840 by John Bennet Lawes (1814 – 1900) at the Rothamsted Experimental Station. He studied the impact of inorganic as well as organic fertilisers on crop yield and founded one of the first artificial fertiliser manufacturing factories. Fertiliser, in the form of Chilean nitrate or guano (birds droppings) was imported by Britain. The first commercial process for fertiliser synthesis was the production of phosphate from the dissolution of coprolites or fossilised faeces in sulphuric acid [Wikipedia].

During the first half of the 20th century, big firms in the USA and Europe turned themselves into transnational corporations by investing in other countries, rather than merely exporting their products. Since the 1980s, the transnational crop companies have increasingly become global players. In developing countries, liberalisation dismantled official controls over commodity markets and tariff barriers, leading to a rapid expansion of global trade in foodstuffs. Big retailers began organising new supply chains to source fresh produce from developing countries. Additionally, they expanded in the larger countries of the developing world to serve the needs of the new middle classes. Recently, much of the action has shifted to the developing world, more particularly to China, which has become the leading market for commodities. New global players are emerging and at the same time, the digital revolution and biotechnology are redefining the sector. Big data and intelligent data treatment systems result in the emergence of new external players.

Despite their all-embracing power, the food majors have so far paid little attention to the impact of their actions on the world at large. They should also address issues such as hunger, malnutrition, environmental quality and climate change, waste disposal, sustainability, health and disease, as well as social justice. These concerns have clearly been highlighted by social movements, international conventions and civil society organisations. The latter exert more pressure than ever before on global corporations by increasingly appealing for changes to be made in current production approaches, marketing methods and purchasing practices.

The Agrifood Atlas reveals a largely ignored aspect of agri-food sector restructuring. Concentration and monopolisation in the agrifood sector [https://www.rosalux.de/en/] are increasingly being driven not by company shareholders, but by private equity firms, i.e. investment management companies that provide financial backing and make investments in the private equity of startup or operating companies through a variety of loosely affiliated investment strategies, including leveraged buyout, venture capital, and growth capital. Typically, private equity firms raise pools of capital or private equity funds that supply the contributions for these transactions. They receive a periodic management fee as well as a share in the profits earned from each private equity fund managed [Wikipedia].

The private equity firm, 3G Capital from Brazil [http://www.3g-capital.com/], controls several of the world’s largest food and beverage corporations. The founding partners of 3G Capital are Jorge Paulo Lemann, Marcel Telles, Carlos Alberto Sicupira, Roberto Thompson, and Alex Behring. The firm has offices in New York City and Rio de Janeiro. Since 2004, 3G Capital has led or accompanied mergers, which have created the world largest beer company (AB InBev) and one of the top three largest fast food companies (Burger King).

In July 2015, 3G Capital partnered with Berkshire Hathaway to complete the combination of H. J. Heinz Company and Kraft Foods Group, forming the Kraft Heinz Company, following 3G and Berkshire’s acquisition of Heinz in June 2013. Previously, in December 2014, 3G Capital completed the combination of Burger King and Tim Hortons, forming Restaurant Brands International, following 3G Capital’s acquisition of Burger King in October 2010. Affiliates of 3G Capital’s Partners have been influential shareholders of AB Inbev since 1989 and Lojas Americanas since 1983 [http://www.3g-capital.com/]. In February 2017, 3G Capital attempted, through Kraft Heinz, to take over its much larger rival Unilever for 143 billion US dollars. The offer was rejected. In 2016, Mondelez, a 2012 Kraft spin off confectionery maker, failed to take over Hershey, a US chocolate maker. These failures have increased the likelihood of Mondelez being reabsorbed into Kraft Heinz.

3G Captial’s takeover strategy is just the tip of the iceberg. Almost all large food companies have launched their own venture capital arms in recent years, investing in smaller, upcoming brands. Aggressive takeovers driven by venture capital have now become commonplace occurrences. Hence, we urgently need (new) regulations, that seriously limit the hold of the financial sector on the agri-food sector.

The increasing size and power of agri-food corporations is threatening the quality of our food as well as the working conditions of the people that produce it. The European Union can and should play a leading part in rejecting these consolidations [Friends of the Earth Europe].

The European Commission currently faces a decision on whether to authorize the potential Bayer-Monsanto mega-merger. European regulators could approve it by early 2018. There is now growing pressure to intervene and block the formation of the agri-food giant. In the recently published study by the University College London, Lianos & Katalevsky [2017] argue that this deal would raise prices and increase farmer dependency on the combined entity. If the deal were to get the go-ahead, just three companies – ChemChina-Syngenta, DuPont-Dow and Bayer-Monsanto – would own and sell two-thirds of the world’s pesticides and 60 % of the world’s patented seeds.

Alternative food production systems are possible and are now being operated by local food producers and farmers across Europe, creating safer jobs and greener farms [Pussemier & Goeyens 2017].

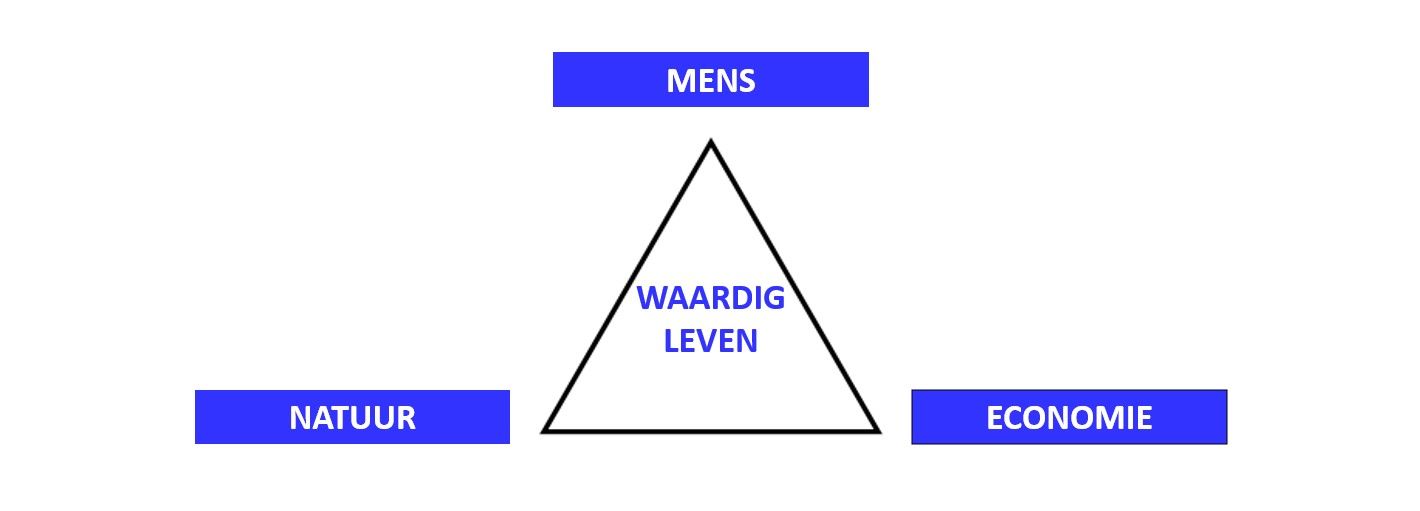

The switch to ecological farming has now become a matter of do or die. This may sound like a peremptory statement. All the same, the agriculture of the future will need to adopt the principles of sustainability. It will occupy a large part of the planet’s mainland as well as its oceans and estuaries, if fishing and aquaculture are also taken into account. Moreover, agriculture employs large numbers of people – many of them farming for their daily food. We simply cannot go on depleting resources, destroying biodiversity and increasing greenhouse gas emissions in the limited area that can and must be reserved for agricultural activities and production.

Intensive industrial agriculture is fuelling and accelerating climate change. The cultivation of new land is being carried out at the expense of pristine areas – the rain forest, for example – which are currently important carbon sinks. Moreover, global warming will lead to substantial losses of arable land (arid zones, areas near or even below sea level); a vicious cycle accompanied by negative social consequences (such as migration) and one that offers little or no escape.

Agriculture will have to be sustainable in the future. And to be sustainable, the laws of Ecology must be observed. Tomorrow’s agriculture will therefore have to be ecological.

Ecological farming is in fact already well under way in European countries: the bio-diversity that can be observed in our fields makes our environment more attractive (see figure); and the care provided to the crops and livestock is becoming more respectful of the environment and animal welfare. European decision makers can play a leading role in rejecting undesirable mega-mergers, since ecological food systems clearly provide a viable alternative.

References

3G Capital, http://www.3g-capital.com/

Heinrich Böll Foundation, https://www.boell.de/en

Lianos & Katalevsky [2017]. Merger Activity in the Factors of Production Segments of the Food Value Chain: A Critical Assessment of the Bayer/Monsanto merger, Centre for Law, Economics and Society, Faculty of Laws, University College London

Pussemier & Goeyens [2017]. AgricultureS & Enjeux de société, Les Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux

Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, https://www.rosalux.de/en/F