The world health crisis caused by the spread of COVID-19 is threatening environmental sustainability

Gorrasi et al. [2021] evidence that the chaos and urgency induced by the COVID-19 pandemic has led to massive fossil fuel-derived plastic production and utilisation, thereby largely ignoring the recent environmental policies. They conclude that society issues can no longer be solved by the “painkiller approach” [Lichtfouse et al. 2010], but require instead a new world system involving fast evaluation and actions taking into account all problem aspects.

Plastic waste, the old problem now requires new momentum

Long before the world knew about COVID-19, millions of tons of plastic debris had ended up in the World Ocean with devastating consequences for the environment and an unacceptable waste of precious resources, including crude oil. Macroscopic degradation residues of common objects such as bottles and food packaging are just a small part of the waste. Most of it consists of micro and nanoparticles and are extremely hard to remove.

These last few months have seen a sharp increase in plastic waste from personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves as well as from plastic shopping bags that are used to prevent cross contaminations. The lockdown has also boosted e-commerce, resulting in greatly increased consumption of containment and packaging materials; moreover, medical waste has also increased dramatically [Silva et al. 2021].

Obviously, the fight against the virus has overshadowed environmental protection policies. Plastic waste is a problem that also involves economic, social and technological aspects [Vanapalli et al. 2021].

The emergency caused by COVID-19 is highlighting the extreme fragility of our systems

To fight the health crisis people need large quantities of inexpensive, safe and readily available materials. The most obvious option given the emergency situation was to use fossil fuel based disposable materials such as polypropylene and polyethylene.

This does not mean that alternatives based on biodegradable materials are not available. Yet, biopolymers are not our first choice when a fast and efficient response to a real problem is required. From a commercial point of view, these materials are not sufficiently well-known; they are also fairly expensive and sometimes difficult to handle. There are still not enough biorefineries capable of rapidly and sustainably supplying the required high volumes at competitive costs, and there are too few companies that are able to recycle these materials. Moreover, many scientists argue that the massive use of biodegradable materials could create serious issues for the small number of existing treatment plants.

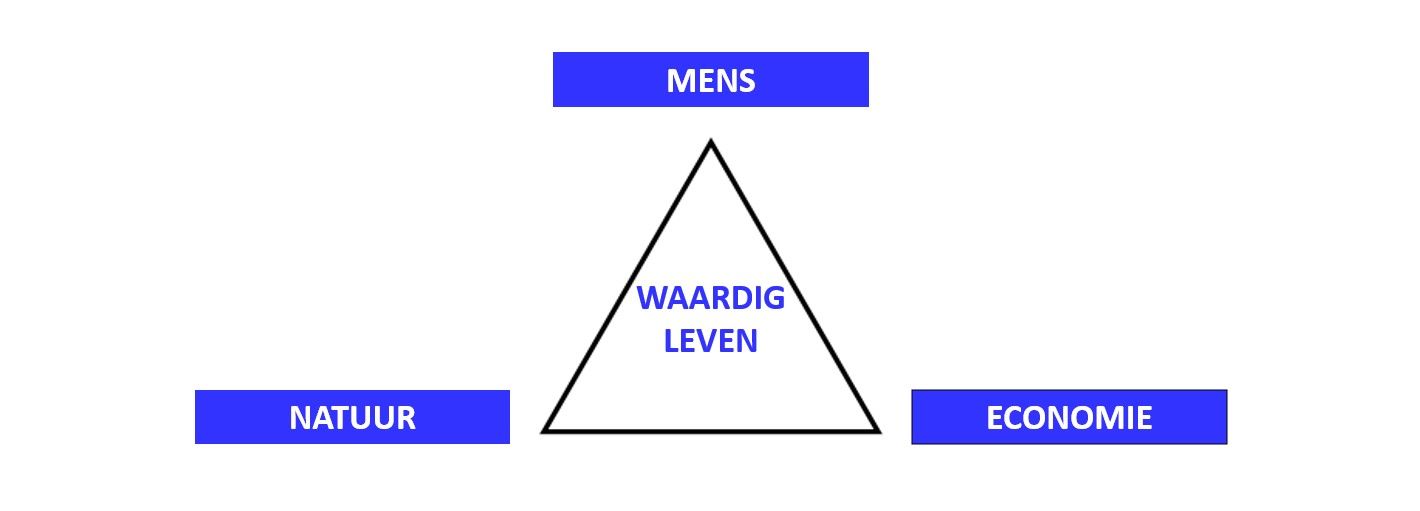

The COVID-19 pandemic has strongly confirmed the limits of the current “take-make-and-dispose” approach and challenges us to rethink and redesign the system as part of a more resilient, circular and low carbon economic model. Circular economy means a whole lot more than minimising the production of waste or inventing biodegradable materials. The circular economy is a radically different economy, which is meant to overcome traditional conflicts between socioeconomic and environmental interests [Aldaco et al. 2020; Ellen MacArthur Foundation 2020].

Only when governments are able to set a clear direction for circular innovation in the private sector, will it be possible to combine economic regeneration, better social outcomes and climate ambitions. Unfortunately, it is obvious that real political willingness to do so is still lacking.

A radical innovation and a radical change in approach are absolutely necessary

In the words of the French philosopher and sociologist, Edgar Morin [2020]: …the mega-crisis caused by the coronavirus is the brutal symptom of a crisis in our earthly (ecological) life… The post-corona period is already being prepared. We should divest ourselves of Barbara Kruger’s 1987 iconic mantra, “I shop therefore I am”, and return to the original statement as produced by René Descartes in 1637, “I think therefore I am” [Gorrasi et al. 2021 and references herein].

If we are to do so, we need to understand the social and environmental values of consumables, we need to keep them in circulation for as long as possible. It is essential to design products/objects that are easier to disassemble and recycle, and to create infrastructures that facilitate the return of products to manufacturers. It is crucial to introduce radical innovation holistically if businesses and governments are to meet circular economy goals.

Will the COVID-19 pandemic spur a rapid transition to new models of circular economy? It is in our interest to deploy urgent and coordinated efforts to develop larger and more efficient systems as well as infrastructures for plastic waste management. Strict policies should force companies to reduce the use of “new” materials in favour of those that come from recycling. Additionally, efficient tax policies could encourage sustainable products and processes.

Plastics remain important, because of the many advantages they provide. Instead of demonising them, we should learn to use them responsibly.

Morin [2020] concludes: … We have entered the era of great uncertainties. The unpredictable future is in the making today. Let us ensure that it is for political regeneration and improvement, for the protection of the planet and for a humanisation of the society. We must change our path…

References

Aldaco et al. [2020]. Food waste management during the COVID-19 outbreak: a holistic climate, economic and nutritional approach, Science of the Total Environment 742, 140524

Ellen MacArthur Foundation [2020]. The Global Commitment 2020 Progress Report, pp. 76

Fernandes [2019]. Microplastics and nanoplastics are polluting your body, here’s how, The CSR Journal, July 8

Gorrasi et al. [2021]. Back to plastic pollution in COVID times, Environmental Chemistry Letters 19, 1 – 4

Lichtfouse [2010]. Society issues, painkiller solutions, dependence and sustainable agriculture, in Lichtfouse (ed.) Sociology, organic farming, climate change and soil science, Springer, 1 – 17

Morin [2020]. Changeons de voie, Denoël, pp. 150

Silva et al. [2021]. Increased plastic pollution due to COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and recommendations, Chemical Engineering Journal, 126683

Vanapalli [2021]. Challenges and strategies for effective plastic waste management during and post COVID-19 pandemic, Science of the Total Environment 750, 141514