It’s all corn !

Well, maybe not all of it is corn. But there’s an awful lot of it hiding in our food. A lot more than we ever suspected. We think our supermarkets offer huge varieties of food. Yet, much of that food comes from one single crop [Michael Pollan 2006]. And it all starts with … corn.

Corn is what feeds the cattle that becomes the meat you eat. Corn feeds chickens, ducks, turkeys and other poultry. Corn feeds millions of pigs housed in commercial pigsties as well as countless non-carnivorous fish raised in fish farms. Corn-fed chickens lay the eggs you eat for breakfast. And corn primarily feeds the dairy cows that produce the milk, butter, cheese, yogurt and ice creams.

But that’s not the end of it. Take any bag of crisps, any candy bar, any sweet biscuit, cheese spread, canned soup, salad dressing, mayonnaise or ketchup and you will see the list of ingredients includes such substances as maltodextrin, monosodium glutamate, ascorbic acid, lecithin, mono-, di-, and triglycerides, fructose-glucose syrup. And guess what? These chemicals are predominantly derived from corn, and if you wash them down with a soft drink, you are drinking corn with your corn. Since the 1980s many soft drinks and most of the fruit juices sold in supermarkets are sweetened with corn syrup.

Though fast food outlets appear to offer a vast range of products, their food and drinks have more in common than we are led to believe. According to an earlier study, the multiplicity of choice conceals the fact that the overwhelming majority of takeaway food items is actually based on one single source: corn.

Corn – whether black, brown or yellow – is a shooting star in the food firmament. For better or for worse is hard to say, though I believe the prevalence of monocultures and intensive livestock breeding cast a worrying shadow over the future of our food.

But are we sure corn is the predominant source? I returned to my huge collection of scientific papers and books and discovered convincing evidence for the overwhelming presence of corn provided by the analysis of stable isotope ratios of food samples. Ten years ago, A. Hope Jahren and Rebecca A. Kraft [2008] from the University of Hawaii discovered the omnipresence of corn by chemically analysing a variety of foods from America’s top chains. I could not help being intrigued: the authors of the paper used the same technology as I did many years ago when researching oceanic nitrogen fluxes for my PhD thesis.

Stable isotope ratio determinations are a surprisingly reliable way of tracing the origins of foods. Like all plants, corn gets its energy through photosynthesis, but it uses a method that differs slightly from other major crop plants like rice, wheat or potatoes. This difference is reflected in the plant’s ratio of two carbon isotopes – the common carbon-12 and rare carbon-13. Corn has a signature ratio that sets it apart from other crops and by association, the meat of animals that consume the plant also stand out in the same tell-tale way. The results clearly showed that most of the cows that ended up in the burgers were fed exclusively on corn. Of 162 samples of beef collected by Jahred and Kraft [2008], only 12 (less than 10 %) came from animals that were potentially fed on other sources, like grass or grains. And there were no exceptions for chickens; they had all had nothing but corn.

The same scientists also measured the levels of stable nitrogen isotopes in both chicken and beef burgers. The high levels they found indicated that the animals were fed with corn that had been grown using nitrogen-based fertilisers, and that they had been reared in very confined spaces. The fertilization required for corn production results in nitrogen-15 enriched (i.e. the rare nitrogen isotope) corn seed and silage compared with natural vegetation. Moreover, beef produced in confinement was enriched in nitrogen-15 compared with animals raised outdoors.

Interesting results. But do they really matter? One could argue that consumers have a right to know where their food comes from. Obviously, most of our food can be traced back to corn monocultures and intensive livestock farming.

This we know. But it is imperative that the situation should change and that it should change as soon as possible!

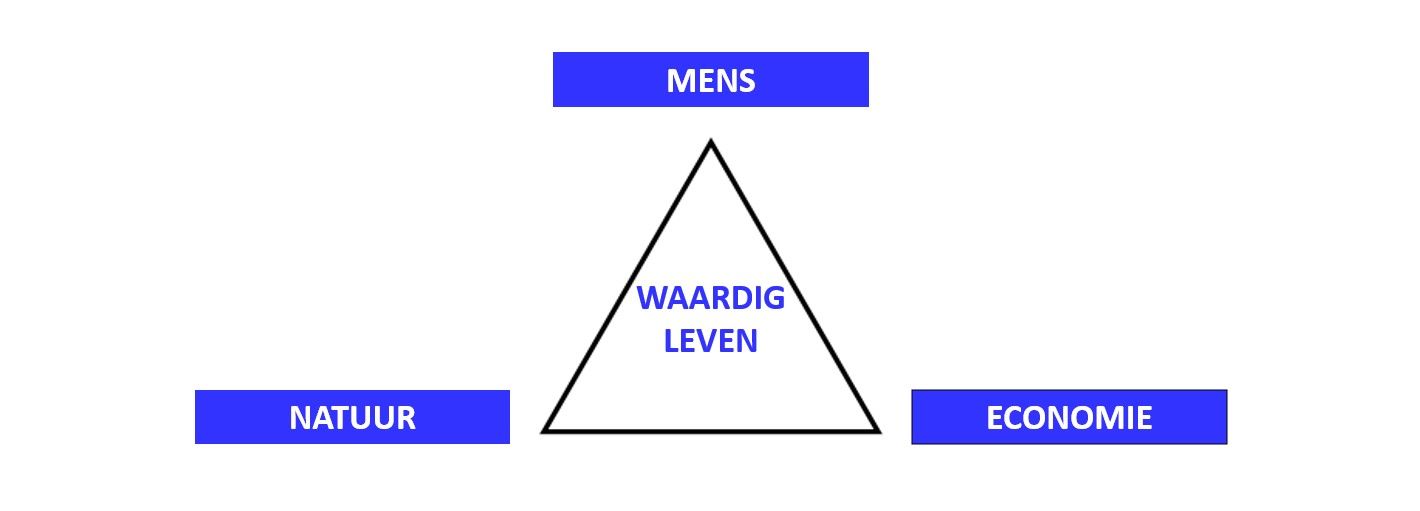

There is simply no alternative to ecological agriculture. This may sound very final, but it is clear to me that agricultural practice has only one possible future: sustainability [Luc Pussemier and Leo Goeyens 2017].

Sustainability refers to ecology: we have to use our natural resources sensibly and abandon linear economy for circular economy; we need to drastically reduce our greenhouse gas emissions and respect and preserve biodiversity in the limited space that can and must be reserved for agricultural production.

Jahren & Kraft [2008]. Carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes in fast food: Signatures of corn and confinement, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, 46, 17855 – 17860

Pollan [2006]. The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals, Bloomsbury

Pussemier & Goeyens [2017]. AgricultureS et Enjeux de Société, Presses Universitaires de Liège